As conflict worsens in eastern Congo, 2 armed groups pledge to respect civilians

- Update Time : Saturday, 30 March, 2024, 01:11 pm

- 65 Time View

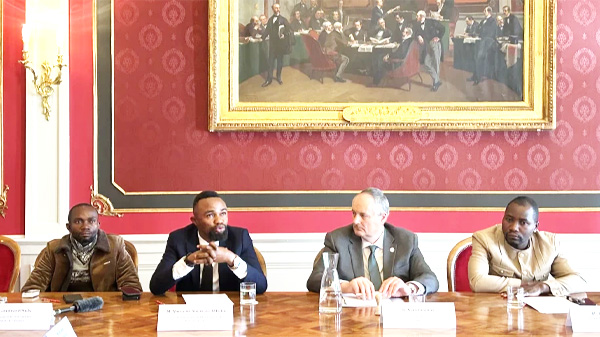

Online Desk: Under a crystal chandelier in a hall where the first Geneva Convention was signed in the mid-19th century, representatives of two armed groups in Congo signed solemn pledges this week to both their violence-wracked country and the wider world: We will do better to respect and protect civilians.

With several Western diplomats looking on, the envoys made commitments that their forces will work to end sexual violence, food insecurity and conditions of famine and to ensure greater access to health care in the parts of increasingly violent eastern Congo that they operate in and control.

The ceremony Tuesday at City Hall in Geneva, a Swiss city that’s known for an internationalist bent and as home to the international Red Cross, is the culmination of years of work by the humanitarian group Geneva Call, which works to protect civilians in conflict zones.

Congo, Africa’s second-largest country, has seen a recent upsurge in insecurity in its mineral-rich east, an area that has been wracked by conflict for decades. More than 120 armed groups are fighting for land and power and, in some cases, protecting their communities. However, M23, the largest and best-known group, allegedly linked to neighboring Rwanda, has not engaged with Geneva Call.

President Felix Tshisekedi, who started his second five-year term in January, had made quelling violence in the eastern parts of the Central African country a priority in his first term — but has struggled to deliver results.

In Geneva, two armed groups that are loosely aligned with the government against M23 inked separate “Deeds of Commitment” on the rules they’ve vowed to respect. Geneva Call was quick to say these are not formal agreements and don’t “legitimize” the armed groups.

One of the two, CMC-FDP (the French language acronym for Collective of Movements for Change/Self-Defense Force of Congolese People), has worked with Geneva Call for five years and taken steps such as releasing 35 children who were formerly in the group and rehabilitating schools and health centers.

“We are here as representatives of a patriotic resistance group in the Democratic Republic of Congo and we’re here in Geneva to reiterate our commitment to respect international humanitarian law and human rights.” said Jimmy Didace Butsitsi, an assistant to the group’s president, Christophe Mulumba.

The larger of the two groups is NDC-R/Guidon (Nduma Defense of Renewed Congo/Guidon), which has about 5,000 fighters. It has released over 20 hostages, undergone training in humanitarian law, and handed over 53 “perpetrators” of sexual or gender-based violence in its ranks to authorities as part of its work with the Geneva group.

“Before all these training courses that we’ve taken, we could let ourselves do whatever we wanted,” said group spokesman Marcellin Shenkuku N’Kuba, who was accompanied in Geneva by Jérémie N’Kuba, the group’s political chairman. “Now, we feel — we can see — there’s a change on the ground, and so we can’t let ourselves do whatever we want anymore.”

Shenkuku N’Kuba acknowledged that respecting the commitments “isn’t easy” and said he’s “not a prophet” but that the group will endeavor to adhere to them now that the pledges have been made.

He said his group was also motivated out of a desire to debunk preconceived notions that people around the world might have about resistance groups, and “show our desire and to influence others also to adhere to the philosophy of respect for human rights … despite the circumstances our country is going through for the moment.”

Alain Délétroz, Geneva Call’s director-general, said the idea behind such commitments is “to encourage other groups to follow the examples of these bigger groups.”

The humanitarian group was born in 2000 out of an effort to ban landmines, and it has shepherded nearly 120 such pledges from armed groups in countries, including Iraq, Myanmar and Syria, on issues like child protection, sexual violence and gender discrimination.

Geneva Call will keep tabs on any signs that the two groups might be violating their commitments, and would first raise any issues with their leaders confidentially. If troubles persisted, the aid group could go so far as to “repudiate” the deeds — but that has never happened in any other country.

The ceremony took place in the City Hall’s “Alabama Room,” under a painting that commemorates a meeting of bearded and mustachioed envoys from Europe and the United States who signed the first Geneva convention on aid to war-wounded in 1864.